By Shelley Neese

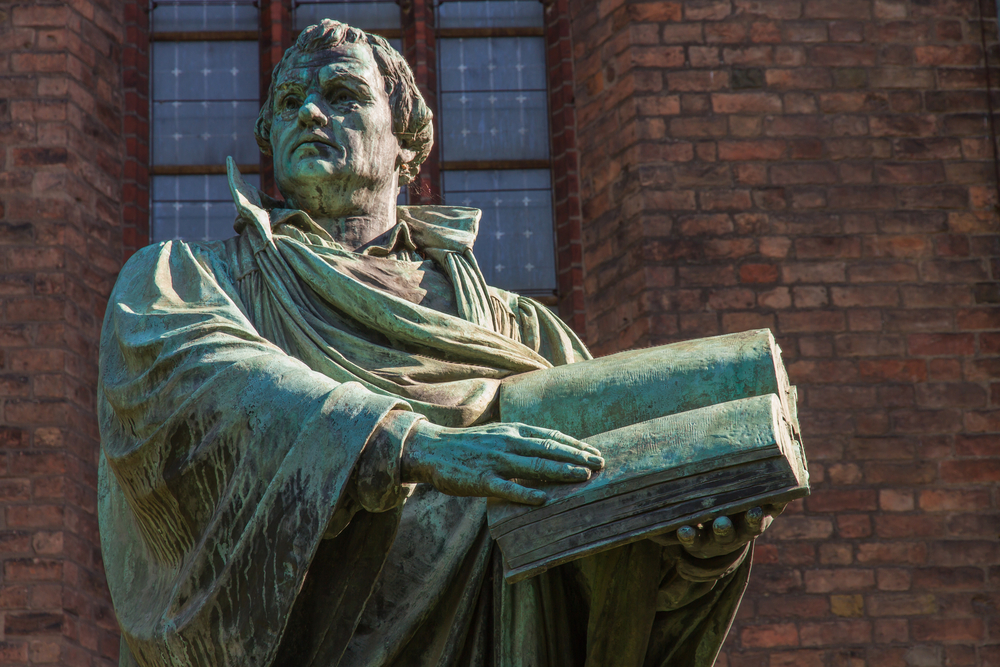

At 34 years of age, the Martin Luther of 1517 was a little known Augustinian monk plagued by thoughts of his own sins and failings.

Luther, in his own words, suffered from an “extremely disturbed conscience.” When his private meditations on the scriptures revealed to him that righteousness was a gift from God, born out of grace through faith in Jesus, he was relieved from his own damnation, but convinced more than ever that he had to work to eradicate false doctrine.

The Ninety-Five Theses is credited for sparking the Protestant Reformation. However when Luther nailed the Theses to the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, his intention was merely to hold a public scholarly debate on the commercialization of the Church by its selling of indulgences.

In the rapid succession of events that followed, Luther was propelled from challenging Church practices to condemning the Church itself. Aided by the rise of the printing press, the prolific writings of Luther spread like a firestorm throughout Europe to a growingly literate public starved for teaching. In 1521 Luther was summoned to trial by Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms. Asked if he was willing to recant and retract his opinions on the Catholic Church, Luther famously replied, “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason, I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God.”

With this rebuttal, Protestantism – the Christian doctrine to which I have always subscribed – was born.

LUTHER AND THE JEWS

As a Protestant, I have tortured feelings regarding the person of Martin Luther.

Luther must be credited for the revolution in Christianity that brought the Bible back to center stage. His eloquent teachings on salvation and justification may be taken for granted today but they were nothing short of earth-shattering in 16th-century Europe.

However, Luther had many personal shortcomings.

A hypochondriac known for his hot temper and manic behavior, Mark A. Noll in his book Turning Points writes, “it is not for propriety or diffidence that Luther is remembered in the history of Christianity.”

However, it is Luther’s hateful teachings on the Jews that forever blacken his name, tainting his Reformation success.

In the earlier years of his life, Martin Luther condemned the Catholic Church for its treatment of the Jews and deemed Jewish obstinacy toward conversion as reasonable given their torturous treatment at the hands of the papacy. In his article “Jesus Christ was born a Jew,” written in 1523, Luther sympathized with Jewish history, saying, “if I had been a Jew and had seen such dolts and blockheads govern and teach the Christian faith, I would sooner have become a hog than a Christian.”

Because of statements like these and his love for Hebrew, Luther’s Catholic enemies accused him of being a crypto-Jew trying to destroy the papacy.

Luther, no doubt, believed that a Reformed Christianity stripped of false doctrine and bound to the Scriptures would attract Jews to convert voluntarily. He often protested against forced conversion. He defended Jewish integrity saying, “the Jews are blood-relations of our Lord; if it proper to boast of flesh and blood, the Jews belong more to Christ than we.” At some point, Luther even met with Jewish apologists to explain his interpretation of certain Old Testament messianic passages. When they refused to accept his exegesis over their Talmud, Luther refused to ever meet with Jewish leaders again.

When Jewish converts never materialized and Jews were no more inclined to Protestantism than Catholicism, Luther’s views changed radically. A disillusioned Luther became a loudspeaker for the world’s most ancient hatred. He began preaching violent anti-Semitic rants, publishing five treatises on the subject. In 1543, three years before he died, Luther wrote On the Jews and their Lies. Luther was known for a coarse writing style – a style popularized in that century with its many pamphlets – but this paper went to new depths and can arguably be called the first popular work of modern anti-Semitism.

He warned Christians to be on their guard against Jews since in their synagogues “nothing is found but a den of devils in which sheer self-glory, conceit, lies, blasphemy, and defaming of God and men are practiced most maliciously.” Luther claimed the Jews had sunk into “abysmal, devilish, hellish, insane baseness, envy, and arrogance.” He said they were “full of the devil’s feces” and the synagogue was an “evil slut.” He went on with such poisonous rhetoric for 65,000 words.

Luther called on princes and nobles to burn down synagogues and Jewish schools, raze Jewish homes, forbid Jewish teaching or texts, confiscate Jewish wealth, and expel Jews from Germany. He at one point even regrets their survival: “we are at fault in not slaying them.” Luther’s last words ever spoken from a pulpit was a declaration that if Jews refused to convert “we should neither tolerate nor suffer their presence in our midst!” Going beyond mere suggestions, Luther was complicit in driving Jewish citizens from Germany where he could.

It’s difficult not to read Luther’s invective – calling Jews “poisonous envenomed worms” – as a blueprint for the Nazi Final Solution which came four centuries later. British historian Paul Johnson said Luther provided “a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust.”

Luther’s biographers offer various explanations to justify his radical shift from praising the Jewish contribution to Christianity to calling for their expulsion from Germany. Reformation historian Heiko Oberman in his book Luther: Man between God and the Devil paints a portrait of a man who could work himself up into a tirade about almost any subject, from papists to lawyers to Turks. Analyzing his diatribes against the Jews, Oberman believes Luther was against Jews from a theological standpoint – hating them for their alleged heresy – but not anti-Semitic in the modern racial sense. Either way, Luther’s hatred fits the general definition of anti-Semitism as an irrational hatred of Jews.

Some of Luther’s defenders dismiss his late-term Jewish obsession as a result of his many maladies. Historian Mark U. Edwards claims the increasing vitriol in Luther’s later writings directly matches the deterioration of his health. At best, this defense only tries to clear his name by pleading insanity.

Many scholars have written on the relationship between Luther’s writings and the Nazis’ racial anti- Semitism, a task which fills volumes as one must account for the vast changes in political and religious life in Germany over four centuries. Without recapitulating those contents, the general consensus is that the writings of Luther stoked the flames of anti-Semitism early in Germany’s history. At the very least they provided ready-made propaganda to warrant Hitler’s program of Jewish annihilation.

Though On the Jews and their Lies had been dormant for 200 years, the Nazis resurrected Luther’s texts for their own purposes, displaying them during Nuremberg rallies. Hitler’s education minister, Bernhard Rust, claimed Luther as a German nationalist, saying “I think the time is past when one may not say the names of Hitler and Luther in the same breath. They belong together; they are of the same old stamp.”

Pastors in Germany’s Lutheran churches during the 1940s invoked Luther’s teachings to turn even racially Jewish Christians away at their doors. In one of his speeches, Hitler himself described a new German religion: “I do insist on the certainty that sooner or later – once we hold power – Christianity will be overcome and the German Church established. Yes, the German church, without a pope and without the Bible, and Luther, if he could be with us, would give us his blessing.”

An anachronism, to be sure, but those coarse words still make this Protestant cringe with wonder.

Although the fact that Nazis fostered a secular racism is a redundancy worth continually repeating, the earliest seeds of Jew hatred go back deep in Christian history.

Hitler, crediting his own Catholic faith, once noted, “I am moving back toward the time in which a 1,500-year-long tradition was implemented – and perhaps I am thereby doing Christianity a great service.”

However, what the Reformation’s tainted history proves is that the roots of the Holocaust reach deep into the Catholic and Protestant traditions.

In their book Why the Jews? Dennis Prager and Joseph Telushkin note, “it is instructive that the Holocaust was unleashed by the only major country in Europe having approximately equal numbers of Catholics and Protestants.” Both faiths share the blame for breeding a culture of anti-Semitism that readied the majority of Christian eyes to go blind when it came to the Nazi roundups of their Jewish neighbors.

THE REFORMATION AND THE JEWS

In the short term, Luther and the shakeup of the Reformation had a negative effect for the Jews of Germany and Europe. In the wake of the 16th century’s religious upheaval came political and geographical changes and the birth of German nationalism. The German nobility quickly rallied to Luther’s aid with the aim of throwing off Rome’s heavy hand altogether.

Luther believed the alliance to be beneficial in that the nobility could use their positions to assist with Church reform.

Jews were forced to show their hand and pick a side: Emperor Charles V and his imperial army or the German nobility with their Protestant patron. They choose to provide the emperor with money and supplies because of his recent acts of protecting them against expulsion. After the German nobility’s victory over the Holy Roman Empire, the Jews were left on the losing side and labeled enemies of the state.

In the long term, however, the Reformation in many ways benefited the Jews – if for no other reason than that it divided the house of Christendom. The Reformation in Germany spawned a radically new Christian religion and unintentionally that breakaway movement splintered off into other separate movements (Calvinism being the prime example).

In general, anti-Semitism did not plague the English, Dutch, or Swiss Reformations the same way it did German Lutheranism. Second generation Reformer John Calvin and Huldrych Zwingli never articulated a Luther-like theology towards the Jews. Even so, the most promising effect for the Church’s most ancient enemy was the eradication of a universal Christian church and the beginning of secular government freed from Church control. In Johnson’s tome The History of the Jews, he says that the breakup of the monolithic unity in Europe “ended the exposed isolation of the Jews as the only nonconformist group.”

Jews also stood to benefit from the Protestants’ emphasis on Scripture, all of it. These Protestants wanted to bring Christianity back to the point where they believed everything went wrong and set it aright.

This meant casting aside the rituals and hierarchy of Catholicism and reinterpreting the New Testament through the lens of the Hebrew Scriptures. Increasingly literate laypeople were consuming with enthusiasm the stories of the patriarchs, the Exodus, and prophets.

Jewish practices and beliefs became less foreign as Protestants celebrated the Biblical narrative which was now available to them in their own language.

Within Protestantism a subset of scholars arose that although not totally philo-Semitic at least felt there was something to learn from the Hebrew roots of Christianity. Johannes Reuchlin and Andreas Osiander – scholars whose tradition I more closely follow – are prime examples. To read the Hebrew Scriptures in their original language and historical context, Hebraists (as these Christians came to be known) solicited the teaching of rabbis and Jewish theologians.

Rejecting the Holy See’s traditional interpretations, they wanted to find the lost meanings of the Bible.

Some of these Hebraists – like the Anabaptists – went so far as to adopt certain Jewish laws, like circumcision and the Sabbath of rest. For this, Protestantism was accused by Catholics as being a Jewish movement.

Luther was horrified to find the extent to which some of his followers were taking their Old Testament studies. He worried that these Christians were vulnerable to Jewish proselytizing and already contaminated by Jewish thought. In reaction he wrote in 1538 Against the Sabbatarians, where he gave his scriptural argument for why God had “forsaken” the Jews. He also said that it was reasonable to assume that for the 1,500 years since Jesus, God had paid the Law “no heed.” After Luther published Against the Sabbatarians, he vowed “to write no more either about the Jews or against them.” How I wish that the principal architect of Protestantism paid heed to his own advice.

Some Protestants choose to highlight Luther’s earliest writings where he defends and affirms the Jews. They ignore his later writings, dismissing them as a product of his old age or worsening mental defects. Many have simply never heard about the monk-turned-reformer’s position on the Jews, and once confronted are tempted to defend the early Luther and reject the later. It is for those Christians that I am writing.

The reality is that Luther’s anti-Semitism can’t simply be ignored or dismissed on account of his perceived senility. The haunting persistence of his end-of-life diatribes were the putrid Protestant fertilizer that allowed the roots of anti-Semitism to thrive in 20th-century German soil. We, Protestants, must accept Luther’s Jewish theology for what it was and reject it for what it isn’t: anything resembling the loving essence of the Christian faith founded by a Jewish messiah.

Shelley Neese is the author of The Copper Scroll Project and President of The Jerusalem Connection.